The Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2025–2030 (DGA) propose a simplified dietary model strongly focused on increasing protein intake and reducing ultra-processed foods. While these objectives are generally agreeable, a critical analysis of the document highlights several inconsistencies with established evidence in the field of nutritional prevention. In particular, issues emerge regarding the lack of qualitative distinction between protein sources, the communication of risks associated with the consumption of red and processed meat, the handling of the alcohol topic, the graphical representation of cereals, and the equation of different types of fats. This contribution discusses these aspects by comparing the DGA with the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO), the Italian Society of Human Nutrition (SINU), and the new Mediterranean Diet Pyramid (2025), highlighting clinical and public health implications.

High protein intake: quantity without quality?

One of the central elements of the DGA is the increase in recommended protein intake (up to 1.2–1.6 g/kg/day). While an increase in protein may be justified in specific populations (elderly, sarcopenia, athletes), its extension to the general population raises significant questions. The document does not make a sufficiently explicit distinction between animal and plant protein sources, treating them as a functionally equivalent group. However, scientific literature shows that the origin of proteins significantly influences:

- the lipid profile and intake of saturated fats;

- cardiovascular and cancer risk;

- the composition and functionality of the gut microbiota.

WHO and SINU guidelines, as well as the Mediterranean model, instead emphasize the importance of favoring plant protein sources (legumes, nuts, seeds), fish, and only moderately, foods of animal origin.

Red and processed meat: a communication risk

The DGA emphasize the concept of “proteins” without sufficiently explicitly associating the risks linked to excessive consumption of red and especially processed meat. This communication approach is critical, as these foods are associated, according to numerous pieces of evidence, with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and cancers (particularly colorectal cancer).

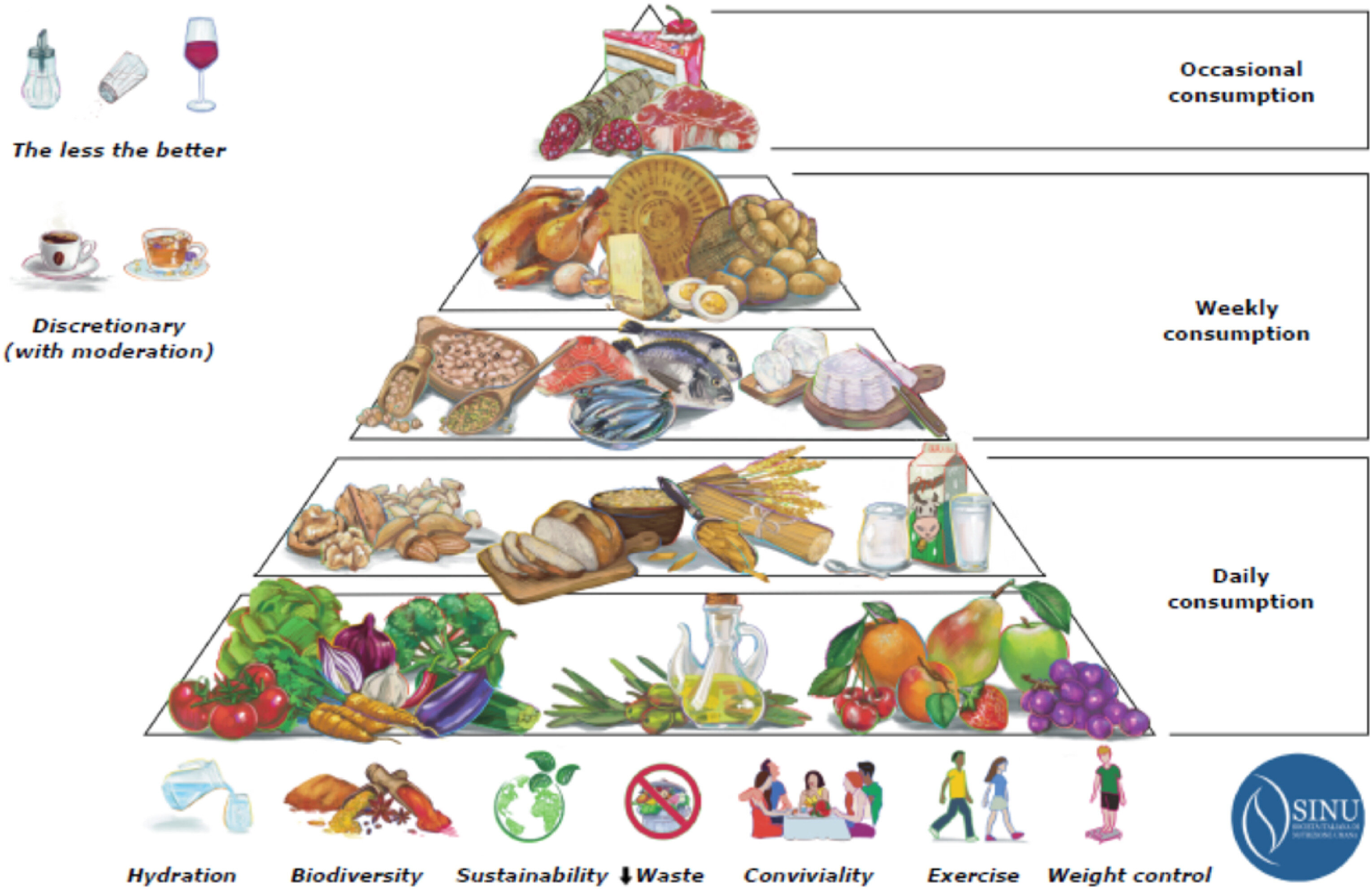

The Mediterranean model and WHO recommendations clearly indicate the need to limit red meat and minimize processed meat, placing them at the highest (and least frequent) levels of the food pyramid.

Alcohol: the absence of thresholds as a public health issue

A further critical point of the DGA 2025–2030 concerns alcohol. The document proposes generic reduction guidelines, without clear quantitative thresholds. This approach diverges from the most recent WHO positions, according to which there is no completely safe level of alcohol consumption for health. From an educational and clinical point of view, the absence of quantitative references can lead to a underestimation of risk, especially in cultural contexts where alcohol consumption is normalized.

Condiment fats: the confusing equation

While recognizing the value of oils rich in unsaturated fatty acids, such as olive oil, the DGA also include animal fats (butter, beef tallow) among the condiment options. This equation is problematic, as these fats are rich in saturated fatty acids, whose excessive consumption is associated with an increased cardiovascular risk.

In contrast, the Mediterranean Diet identifies extra virgin olive oil as the daily reference fat, not as an optional choice among equivalent alternatives.

Cereals: correct content, weak communication

The DGA include recommendations in favor of whole grains and fiber intake. However, their graphical representation places them in a marginal position, with the risk of reinforcing the already widespread idea that cereals are foods to be limited or avoided.

In the Mediterranean model and SINU guidelines, whole grains instead represent a structural component of the daily diet, fundamental for metabolic and gut health.

Clinical and public health implications

Overall, the DGA 2025–2030 risk:

- promoting a high-protein model without adequate qualitative distinction;

- reducing the structural role of whole grains and legumes;

- normalizing the consumption of saturated fats as a daily option;

- weakening the preventive message on the risks of alcohol.

These elements appear to be in contrast with the most established evidence in the field of primary and secondary prevention.

The communicative simplification of the DGA 2025–2030 represents an attempt to improve adherence to the guidelines, but risks sacrificing fundamental qualitative aspects. The comparison with WHO, SINU, and the Mediterranean Diet highlights the need for an approach that does not limit itself to “how much” to eat, but clarifies what, how often, and with what long-term implications.

What to do in practice (Mediterranean style)

For the general population and for clinical practice:

Proteins:

- favor legumes (≥3–4 times/week), fish, and nuts;

- limit red meat (≤1 time/week) and avoid processed meat (or limit – 1 time per month/special occasions).

Fats:

- use extra virgin olive oil daily as the main condiment;

- reduce butter and other animal fats to occasional uses.

Cereals:

- include whole grains at every main meal, adapting portions to the clinical context;

- avoid generalized demonization.

Alcohol:

- communicate that the safest choice is not to consume;

- alternatively, occasional and conscious consumption, not daily.

Global approach:

- favor complete and culturally sustainable dietary patterns, rather than single nutrients.

.jpeg)